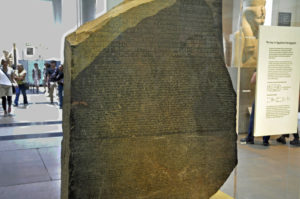

Rosetta Stone in London’s British Museum (Photo by Don Knebel)

As visitors to Egypt know, the walls of its ancient temples and monuments are covered with hieroglyphs. After Christians closed the temples in the fifth century, knowledge of the hieroglyphs’ meanings was lost. Despite extensive efforts, scholars were unable to make any sense of the 1000 symbols, most assuming that each symbol represented a different word or person. In 1799, a soldier in Napoleon’s army found a broken stele, weighing about 1700 pounds and made of pink granodiorite, near the town of Rosetta in the Nile Delta. After the British defeated the French in Egypt in 1801, British soldiers obtained the Rosetta Stone, which they carried aboard a captured French frigate to London. They presented the stone to King George III, who donated it to the British Museum.

The Rosetta Stone includes three sections of inscribed text, the top section in hieroglyphs, the middle in ancient Egyptian Demotic script and the bottom in Greek. Scholars quickly understood the Greek section to be a proclamation issued on behalf of Pharaoh Ptolemy V in 196 B.C. Although scholars assumed the top section contained the same decree, it was another 20 years before Jean-François Champollion of Paris was able to translate the hieroglyphs, recognizing that the symbols could represent both words and sounds. This discovery eventually led to the translation of all hieroglyphs and a much clearer understanding of Egyptian history and beliefs. Today, the Rosetta Stone, behind glass near the entrance, is the British Museum’s most visited object.

Comments are closed.