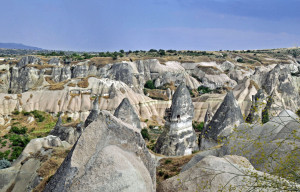

Describing the surreal landscape of Cappadocia is probably the only time the words “fairy” and “church” can be used respectfully in the same sentence. In this region in central Turkey, fairy chimneys can become churches, tunnels can become cities and the incomprehensible can become settled theology.

Cappadocia lies north of the Taurus Mountains, where a series of volcanic eruptions produced a plateau made of thick lava layers. Water and wind then eroded the lava, producing thousands of cone-shaped structures called “fairy chimneys,” some more than 120 feet tall and a few balancing hard caps on their improbably pointed peaks.

For millennia, residents of Cappadocia have hollowed out the soft lava of the fairy chimneys to create homes resembling stone tepees, the porosity of the lava providing excellent insulation. After Christianity had come to Cappadocia through the missionary visits of Paul, the interiors of fairy chimneys became churches.

The soft lava of Cappadocia also facilitated the expansion of tunnels into at least 36 full blown underground cities, some extending ten stories below the surface. Originally used by the Hittites almost 4000 years ago, these cities were occupied by early Christians, perhaps to hide from Roman persecutors.

After Christianity became legal, Cappadocians helped resolve a theological controversy. When the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D. decreed that God and Jesus were of the same substance [homoousios], many Christians objected, arguing that God and Jesus were obviously different. Theologians from Cappadocia, trained in Greek philosophy and called the “Cappadocian Fathers,” taught that things having the same substance can also have different expressions [hypostases], pointing to gold coins made from the same ingot but having faces of different persons. This conception of “God in three persons,” ratified by the Council of Constantinople in 381 A.D., ended the argument for many Christians.

Today’s visitors to Cappadocia can sleep in hotels carved inside fairy chimneys, tour underground cities with kitchens still black from cooking smoke and admire brilliantly colored tenth century frescoes in dark churches. And people for whom the Holy Trinity is important can thank the Cappadocian Fathers for at least trying to make it more understandable.